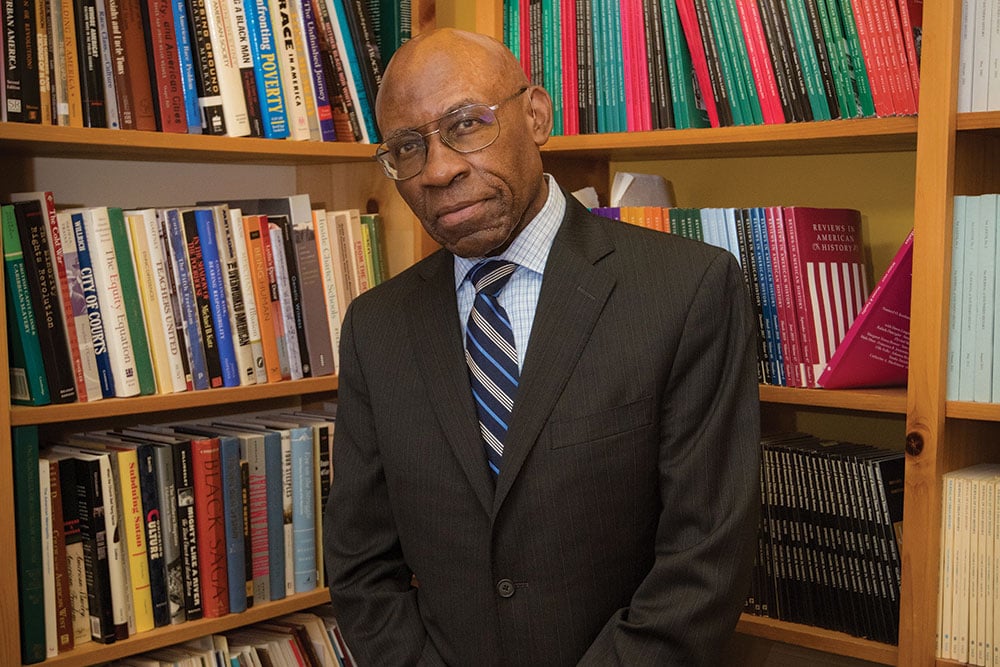

Profile: The People’s Historian, Joe Trotter Jr.

Carnegie Mellon University’s Joe Trotter Jr. is leading a study on reparations in Pittsburgh and how inequality impacted generations of African Americans, including the Black working class.

JOE TROTTER JR. IS THE FOUNDER AND DIRECTOR OF CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY’S CENTER FOR AFRICANAMERICAN URBAN STUDIES AND THE ECONOMY. | PHOTO BY HUCK BEARD

Joe William Trotter Sr. and his wife, Thelma, raised their family in a four-room company-owned house in McDowell County, West Virginia. The couple in 1937 had fled the oppressive sharecropping system of rural Alabama to land a few states away in a situation only slightly better.

The county was deeply segregated, and Joe William Trotter Jr., the couple’s sixth of 12 children, saw his father toil for low wages as a coal loader. But he also saw his father mentor youth and work as a barber, building relationships and counseling other men.

He saw that his father’s contribution to the community went beyond simply supplying manual labor, and he often wondered how broader access to society would have shaped his father’s life.

Those observations propelled him on a mission — as a distinguished historian at Carnegie Mellon University — to document the value of the Black working class and in 2020 to launch a pioneering Pittsburgh reparations study that offers recommendations and rationale for repairing what he calls the damage of slavery and persistent racism in the city of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania.

He is the founder and director of CAUSE — CMU’s Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy — which educates on Black labor and the Black working class. “I think scholars, and society at large, have downplayed the role that working-class people played in the economy, culture and politics. For too often, we’ve only wanted to talk about the role of the teachers, the doctors, the lawyers and so on,” he argues.

Now 78, he has led the call to “acknowledge, redress and offer closure for grievous injustice” — a few factors that shape a leading definition of reparations. The call gained steam following the Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd, which put renewed attention on historical and contemporary inequality.

Pittsburgh’s study is part of the $5 million A.W. Mellon-funded “Crafting Democratic Futures Project,” a broader initiative that looks at nine areas across the nation and engages colleges in community-based reparations solutions. Some of the other institutions include Emory University and Spelman College in Atlanta, Rutgers University, University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and others.

The project explores three critical periods in the region’s history — enslavement, industrial and post-industrial — that it argues harmed the Black community. The study drew from about 185 interviews of people who lived before the 1950s, supplemented by interviews with others who lived during the late 20th and early 21st century.

“These voices are important in building this case,” says Trotter, “because they represent the voices of people like my father and others like him who not so long ago lived through these challenges.”

Under Trotter’s leadership, humanities scholars, community-based organizations and grassroots social activists, along with a collection of oral histories, seek to show how inequality took root and began to impact generations of African Americans.

Such inequality showed up, says Trotter, in the lack of opportunities for equal pay (via the exploitation of industrial workers) for Black people, who were pushed to the bottom of the economy, working for wages that were lower than whites doing the same job.

“We need to really rectify that,” Trotter says.

The study also highlights the bleak outcomes on health and housing. Black workers were housed in some of the unhealthiest environments in the city, which robbed them and their families of good health and shortened their lifespans. As a result, the report argues, families experienced high rates of infant and maternal mortality. The project also suggests that Pittsburgh’s colleges, like so many other institutions, developed and enforced their own forms of racial inequality that still need to be addressed.

Trotter and the group expect to deliver their report to the A.W. Mellon Foundation in May, followed by the release of a public document to be made available on the CAUSE website.

Some of the preliminary recommendations include engaging in research and restorative action for people of African descent; addressing racial disparities in criminal justice, entrepreneurship, wealth and environmental justice; researching residential segregation; addressing legal land redress; and amplifying descendant voices.

The issue of repair is worth considering, says Tim Stevens, CEO of Pittsburgh’s Black Political Empowerment Project and a longtime local activist for racial and social justice.

“The problems of disparities were never fixed. So, the report helps us acknowledge that there is a problem, that there is damage — some of which is still being done — and that we need sustained measures to deal with it.”

Additionally, Stevens says, some of the collective conditions in Black America such as violence, lack of capital, inequality with imprisonment and access to homes are not by accident.

“If we don’t do the repair, we’ll never stop seeing the harm. There’s been a lot of suffering that should not have been experienced.”

Ervin Dyer is a Pittsburgh-based writer who covers Africana life and culture.